I enjoy scrolling through pictures of friends and family on social media. Birthdays and graduations, grandchildren and vacations, job promotions and anniversaries. Through the years the hairlines recede and the kids get taller, but the smiles remain. It occurs to me, though, that what I’m watching are curated lives. Most of us—me included—only show the very best moments to others. We may seem to have it all together, but behind every photo are challenges, damage, and baggage that every person carries with them.

According to the Mental Health Foundation, 74% of people admit to being so stressed during the past year, they have been overwhelmed or unable to cope. Of those, 51% reported feeling depressed, while 61% said they were anxious. Friends, relatives, health conditions, work and debt were the highest stressors.[1] Younger people feel pressure to succeed. Women feel pressure about their appearance. Middle-age people compare themselves to others. So we carry around these mental burdens, and in the meantime, we present a carefully-measured image to the outside world.

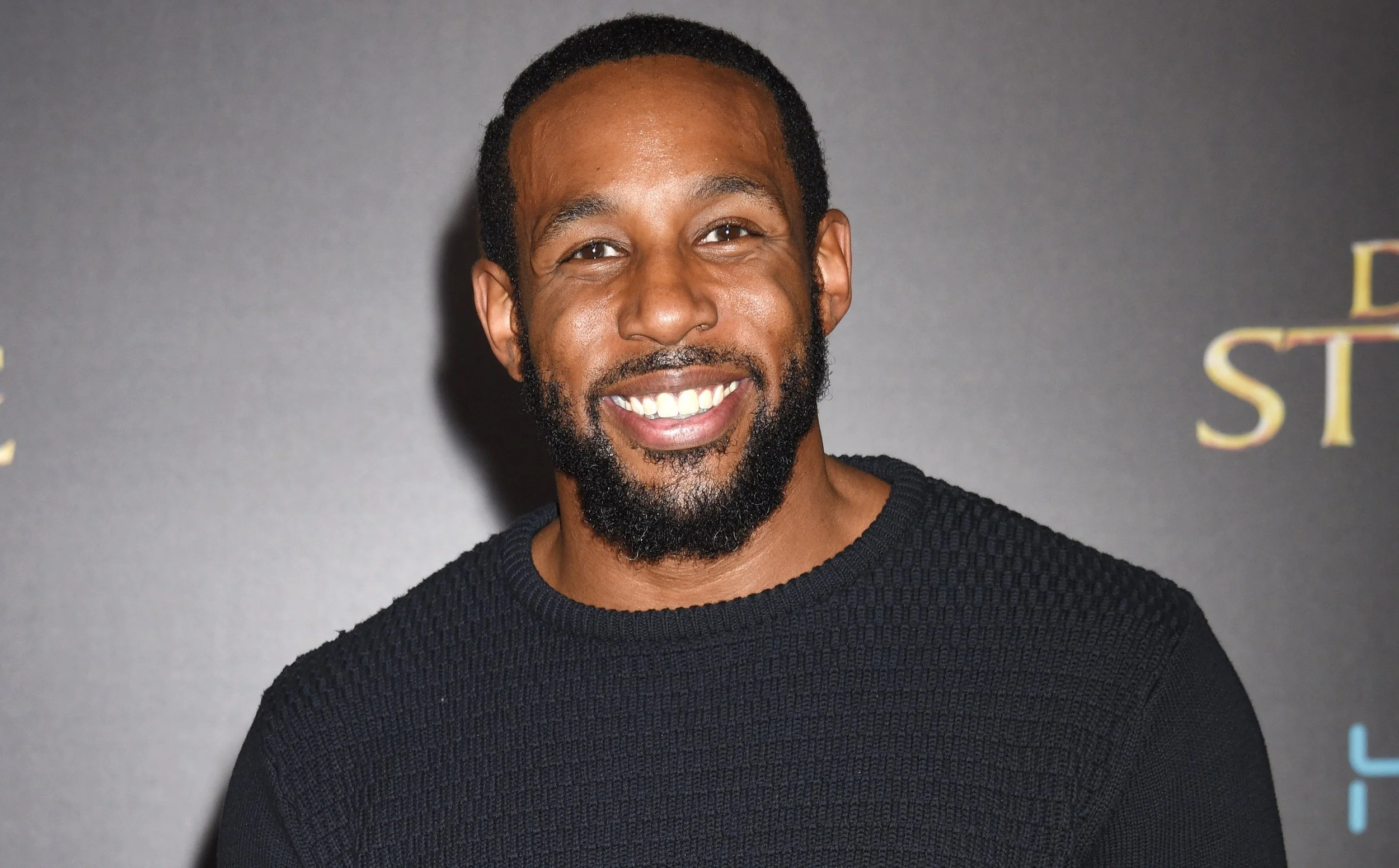

Stephen Boss was a charismatic hip-hop dancer that got his break on the TV show “So You Think You Can Dance”, and went by the stage name “tWitch”. He became a regular on an afternoon TV talk show, and eventually rose to the role of Executive Producer.[2] Behind the scenes, though, he suffered from depression. When his TV gig ended, he began to spiral down, not being able to find a job with similar public exposure. His friend, musician and actor Justin Timberlake, commented, “It’s heartbreaking to hear that someone who brought so much joy to a room, was hurting so much behind closed doors. I’ve known Twitch for over 20 years through the dance community—he always lit everything up. You just never know what someone is really going through.”[3] Stephen “tWitch” Boss’ curated life wasn’t all that it seemed.

For dancer and DJ “tWitch”, everything looked great in life and work—until it wasn’t. Photo: Shutterstock.com

Fine. I’m fine. Everything is fine. We’re all used to living curated lives, and we did it long before social media. Your life today might be a mess, but when someone asks, “How are you doing?”, the answer is often “Fine. I’m fine. Everything is fine.” It’s a curated way of presenting yourself as someone who is able to handle their difficulties on their own. There’s an old joke about a family going to church, arguing and fighting in the car on the way. As soon as they arrive at church, they all straighten their clothes and put on their smiles. Because of course we have to present ourselves as “having it all together”.

Why do we curate our lives? Perhaps it’s because we don’t really believe in others’ concern for our welfare. When someone asks, “How are you doing?” are they really interested in the answer, or just being polite? We long for some meaningful interaction, and a place where we can share our concerns and challenges, without placing a burden on others or making them believe we’re asking them to “fix something”. Scripture tells us to share our burdens with others, because God knows this is good for our mental health and builds strong and faithful relationships. Galatians 6:2 instructs us to “Bear one another's burdens, and so fulfill the law of Christ.”

A relief valve. Have you ever used a pressure cooker? It’s physical science in action. By raising the pressure in the container, the liquid will get hotter without boiling, which means you can cook at a higher temperature without scalding the food. But the pressure can’t get too high, so on top of the cooker is a relief valve that lets off some of some steam while cooking. If that valve wasn’t there, the cooker would eventually explode. In our lives and work, we need a relief valve for the pressures we face every day. We need a way to let off steam, so that we don’t eventually explode.

For people, relief comes through valued relationships. It’s important to be able to share our stresses and strains, and experience care and compassion from others. That relief valve of relationships also helps us focus on people outside of our own needs. Philippians 2:4 clearly tells us, “Let each of you look not only to his own interests, but also to the interests of others.” We simply have to engage with each other, and share our burdens, to keep from exploding under pressure.

The messy picture. In order to cultivate genuine relationships, it’s necessary to cast off the curated life. This doesn’t mean adopting a victim mentality, consistently presenting the worst facets of your life to everyone. But it does mean to quit getting a kick of positive endorphins from the number of likes on your latest social media post. Instead, share your burdens within the body of Christ, with a few trusted believers who you trust and who will be honest, upfront, and helpful to you through your needs. In other words, find a group of people where you can feel safe in saying, “No, not everything is just fine.”

And sharing a messy picture of life means you must also be open to helping others through their messiness as well. This fulfills the Scriptures: “And we urge you, brothers, admonish the idle, encourage the fainthearted, help the weak, be patient with them all” (1 Thessalonians 5:14). You might have heard of this kind of living—it’s often called “being authentic”. That is, not trying to present perfection to the outside world, but instead striving for Christ, and living with the warts in your own life and helping out in the lives of those around you.

A simple gesture. One meaningful means to un-curate your own life and make a positive impact in the lives of others is to pray for them, and connect with them through prayer. On that social media feed, when you see someone have a life moment—a new relationship, a marriage, a new job, a baby born, a friend or relative pass away, a medical emergency—take a moment to pray for them. Then comment your prayer support and a word of encouragement. Praying for those in your orbit is a reminder that every life has challenges. And when you pray, you’ll begin to meet other people of prayer, who will prayerfully engage on your behalf. Before you know it, you’re no longer curating the best moments of life. Instead you’re living in a community of caring people through all of the ups and downs.

Authenticity is the factor in your character that helps you live as your true self. Authenticity helps you to make good decisions, influence others, maintain consistent values, convey a sense of purpose, and have a strong self-awareness.