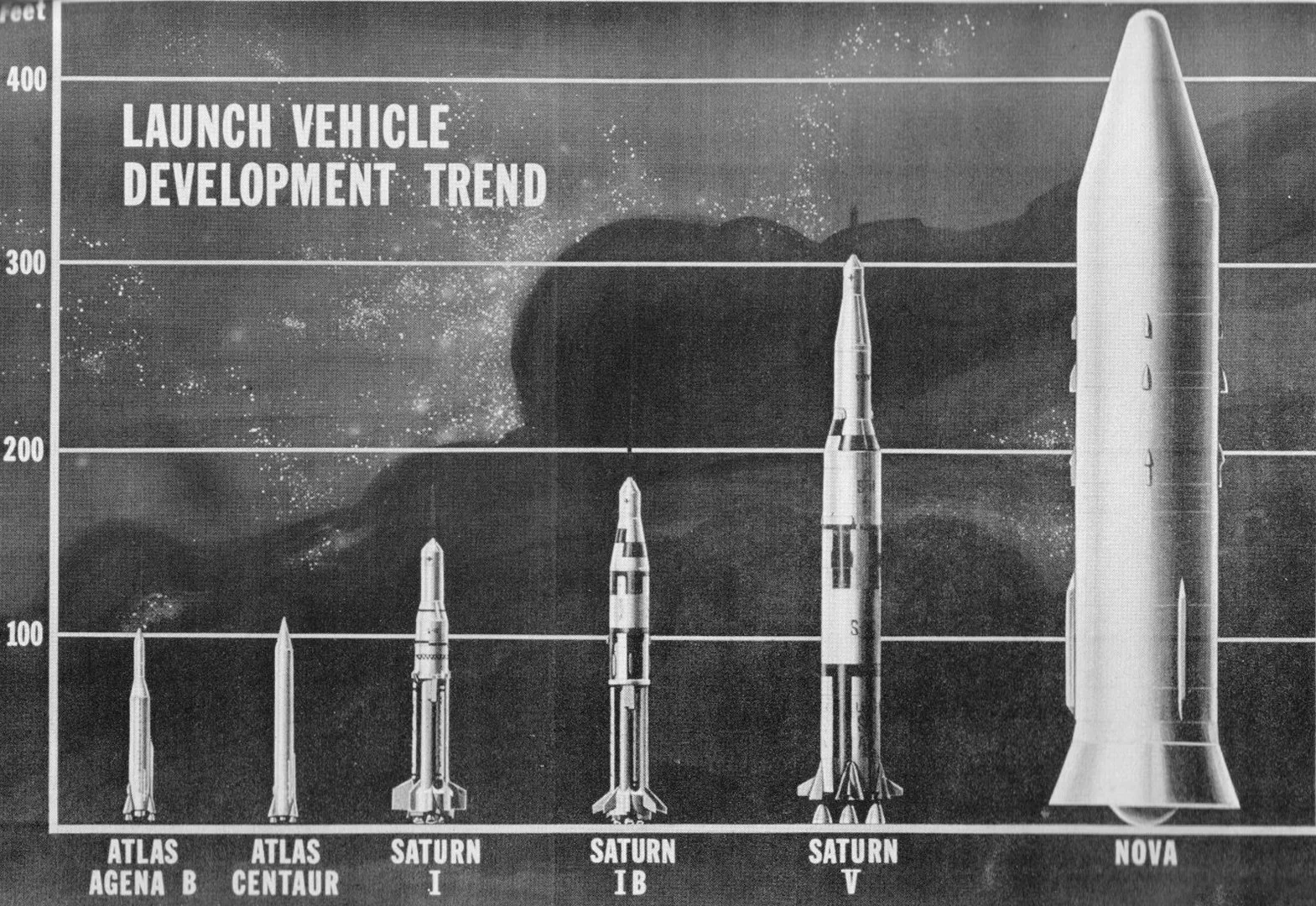

NASA had received a mandate from President Kennedy to go to the moon, and they were figuring out how to do it. One of the important aspects was how to navigate the spacecraft. The first plan was to build a massive rocket that could be navigated from the ground. They’d launch it not just to orbit, but straight to the moon, where the 100-plus ton craft would land and then shoot straight back to earth at mission end. This design, called the “Nova”, was so large, NASA computed that it would shake the concrete launch pad into dust before the craft could clear the tower. It would be 450 feet tall and weigh 30 million pounds. They even considered towing the Nova out to sea and launching it from a floating orientation in the water. But it was too big a leap.[1]

The NOVA rocket would have drawfed the Saturn V. Photo: NASA Public Archive, 1962.

No, they’d have to do things smaller, albeit still at a tremendous scale. They determined to use a plan called “lunar orbit rendezvous”. In this scenario, a craft would launch into earth orbit, then transition to the moon and enter lunar orbit, and then send a smaller craft to the surface. This resulted in the Saturn V launch vehicle—about 80% smaller than the Nova, but still 363 feet high and weighing 6.2 million pounds.[2] Computing the orbits, lunar transition burn, the burn back to earth—all the math would have to be handled in space, and by a computer. But that presented another problem.

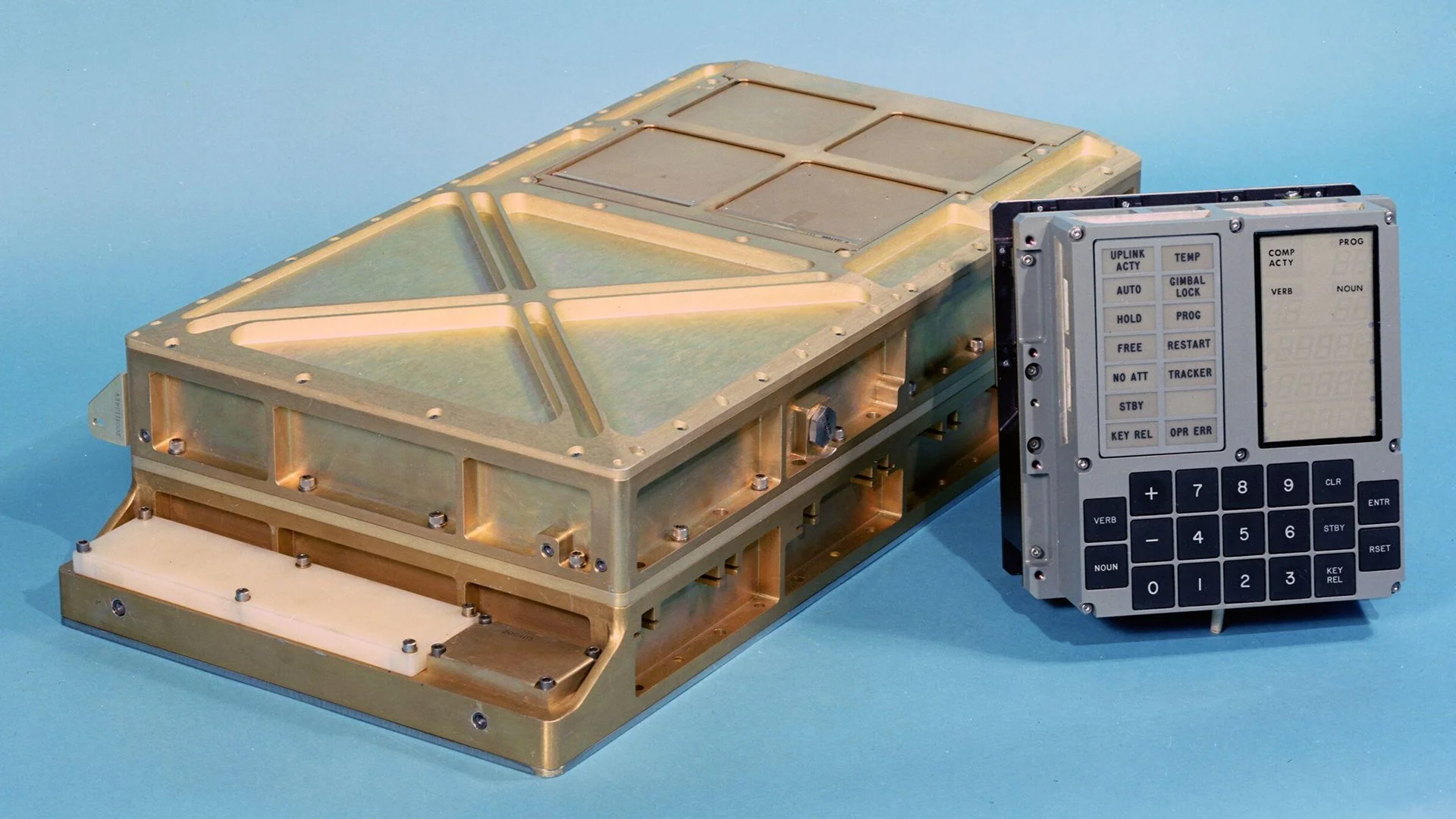

Computers in the 1960s consumed rooms—entire floors of buildings, in fact. They were massive, vacuum-tube laden monstrosities that were amazing for their time, but today would be eclipsed by the chip in your smart watch. The smallest computer in 1962 weighed about three tons and consumed enough power to light up a city block. So NASA commissioned the engineers at MIT to do something unheard of. They’d need to build a new kind of computer, one that would fit in a space the size of a suitcase, consume minimal power, and have the capacity for the complex navigational tasks needed for lunar orbit rendezvous. This “brain” of the spacecraft would be called the Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC), and it would be a revolutionary step in computing that would set the stage for everything from laptops to smartphones to self-driving cars we have today.

The AGC was the first operational computer to use recently-developed silicon chips instead of vacuum tubes. At the tome of its development, NASA purchased 70% of all the silicon chips being manufactured in the US. Fairchild Semiconductor, located in Santa Clara County, California, developed this hardware, and their location and advanced chip development there gave rise to an area that would later become “Silicon Valley”.[3]

The Apollo Guidance Computer was among the first to use integrated circuits on a silicon wafer, the modern computer “chip”. Photo: Wikipedia Commons

Most computers of the time were programmed for a task, and then set to run the computation, and give the answer upon completion. The programming was served up on punch cards. The AGC was different. It had a keypad for input, and could be programmed on the fly. It could also handle more than one task at a time, dividing its computing power among various priorities. Most importantly, though, it’s programming mimicked the astronauts human mind in three key aspects. These programs are still inherent in all computers today, and we are reminded about how we can work and lead looking at the AGC’s revolutionary example.

It could throw out low-priority tasks. The AGC programming was hardwired in the computer with a technique called “rope memory”, threading conducting wire in and out of small loop shaped magnets that translated to binary 1s and 0s. The engineers programmed the ACG to prioritize the most important tasks at each phase of flight. For instance, it needed to think about a navigation adjustment, it would ignore a request to perform a calculation for a later part of the mission. No computer to that time had the capability to put one task ahead of another.

Consider how the leader’s mind works—do you instinctively put high priority tasks ahead of other things? Can you look at four or five decisions before you right now and know which one is the most important? The ability to prioritize is built into every computer today, and mimics the mind’s ability to categorize items by urgency and importance. A method for this was named after President Eisenhower.

The Eisenhower Matrix sorts activities into four quadrants. You Do First (the urgent and important), then Schedule (important but not urgent), then Delegate (urgent, but not important) and finally Delete (neither urgent nor important). This quality made the ACG among the first “smart” computers, and is a simple means for a leader to organize his thoughts and asks around that which is of highest priority.

It preserved critical functions. The ACG took in data and gave answers through the DSKY interface (for “display and keyboard”), throwing out the old punch-card method and giving the astronauts a way to interact with the computer at any time. This “program interrupt” is something we take for granted today. You don’t have to wait on your smart phone to accept an input. You just start typing at any moment and it responds. But this presented a programming issue, as the computer would need to respond regardless of whatever else it happened to be working on at the time an input was received.

To make sure the spacecraft was safe, engineers programmed the AGC to preserve the critical functions of navigation, attitude control and rendezvous. This ensured that if something went wrong, the computer would always complete its primary tasks of keeping the ship headed in the right direction and on target. Again here we see how the AGC and the leader’s brain are similar in arrangement. A leader must also preserve critical functions as he goes through life and work.

The Apollo Guidance Computer enabled the Eagle moon lander to navigate to the surface, despite being overloaded with data input. Photo: NASA Public Archive

Primarily we accomplish this through clarity and vision. That is, we have a keen sense of what is important for our lives and work—our family, relationships, basic needs. And we know the direction we are going—a vision for what we want to accomplish and how we are going to get there. These aspects of leadership make preserving critical functions easy, because we can weigh every task and tangent against that which is most important.

It succeeded despite difficulties. The ACG was an early digital computer and space is unpredictable. The engineers knew that it might become confused or overloaded with commands or data at some point during the mission. Famously, it sounded a “1202 Executive Overflow” alarm during the moon landing itself, as the system became flooded with data from the rendezvous radar. However, it was still able to function by ignoring certain tasks to focus on the landing itself.

This ability to keep going despite obstacles is called resilience, and it exists in leaders as well as in the AGC. Resilience is the capacity to withstand and recovery quickly from difficulties. Mentally we might call this “toughness”. Do you have the ability to weather a storm in life and work, and spring back into shape to overcome? For the AGC this was the result of smart programming. How is your internal “code”? Are you able to prioritize and maintain critical functions in such a way as to overcome those tremendous challenges that are thrown at you unexpectedly?

The smallest computer in 1962 weighed about three tons and consumed enough power to light up a city block. So NASA commissioned the engineers at MIT to do something unheard of.