This series of articles seeks to examine the character attributes of highly successful leaders, regardless of their adherence to a strong faith or moral standard. In presenting these thoughts, Leadership Ministries is not agreeing with or advocating these traits or practices, but rather presents these as ideas for discussion and development in your own leadership journey.

Niels Henrik David Bohr (1885 – 1962) was a Danish physicist who proposed and later confirmed the structure of the atom. He is responsible for the initiation of quantum theory and was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922. The Bohr model of the atom showed that electrons revolve in stable orbits around the atomic nucleus, composed of protons and neutrons. Though other scientists have supplanted his work, Bohr’s underlying principles remain valid to this day.

Philosophy over physics. You may think a theoretical physicist to be shy and introverted. Bohr, however, married Margrethe Nørlund, and the marriage was happy and prosperous. Throughout life, Margrethe was Niels’ trusted adviser. Mathematician Richard Courant, speaking at Bohr’s funeral, commented, “It was not luck, rather deep insight, which led him to find in young years his wife, who, as we all know, had such a decisive role in making his whole scientific and personal activity possible and harmonious.” Niels and Margrethe had six sons. Their son Aage grew up to follow in his father’s footsteps, and shared a third of the 1975 Nobel Prize for Physics.

Much of what we know today of the structure and behavior of atoms comes from the research of Niels Bohr. Photo: Depositphotos

Growing up, despite his early affection for science, Bohr’s parents wanted his education to be well-rounded, and exposed his to historic and contemporary philosophers. Bohr believed that his atomic research could relate to human behavior, and that philosophy could also help to define and explain the atom. His foundational theory of complimentarity, which postulated that atoms may exist in two opposing states simultaneously, led to both philosophical discussions and the beginnings of quantum mechanics.

Bohr’s atomic research touched on the mind-body problem: are our thoughts composed of physical or chemical reactions, or do thoughts exist in the mind apart from our physical brain? In other words, are thoughts matter or energy? Bohr concluded thoughts were, maybe, a little of both—or neither. Of the paradox Bohr once said, “How wonderful that we have met with a paradox. Now we have some hope of making progress.”[1]

You can’t know everything. Some of Bohr’s theories of atomic particles were contradictory, and this bothered the physicists of his day. Einstein in particular took issue with Bohr because he disliked formulas that left anything unknowable. Bohr complimentarity has been acclaimed as the most important scientific concept of the century. As Bohr continued to dig into the nature of the atom, he said that subatomic reality could not be understood in exact numbers because the very act of measuring atomic behavior changed its conditions.

Bohr believed that you could gain knowledge in physics but there would always be some areas that would not be understood because of various limitations. Because his theoretical work was so profound and difficult to understand, Bohr adopted a whimsical approach when speaking and writing, owing to the impossible nature of some of his theories. He once wrote to another physicist, “We are all agreed that your theory is crazy. The question which divides us is whether it is crazy enough to have a chance of being correct. My own feeling is that it is not crazy enough.”

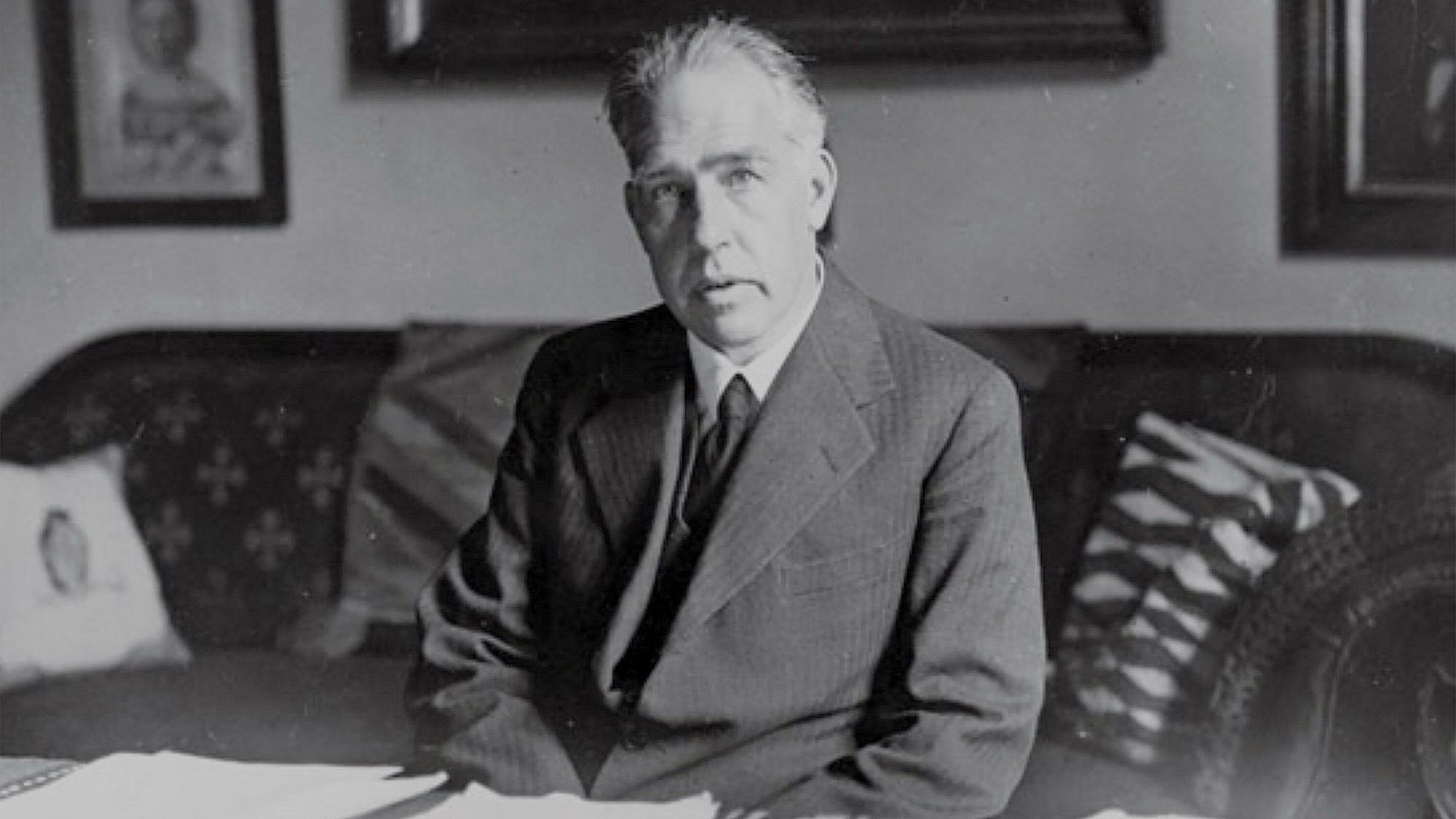

Bohr enjoyed collaborating and discussing his research with other scientists. He was a contemporary of Einstein, and several of his protégés went on to do their own groundbreaking work in physics, including Bohr’s own son. Photo: Public domain

Mentor others in your field. As head of the Copenhagen Institute, Bohr served as a mentor to a number of young physicists. Many of them went on to make significant discoveries of their own. One of Bohr's favorite protégées was Wolfgang Pauli, fifteen years younger than Bohr but very willing to criticize him both jovially with his sharp wit and seriously with his brilliant scientific reasoning. Like many other theoretical physicists, Pauli was inept in the laboratory. Before he became famous for his exclusion principle, he was well known throughout Europe for the "Pauli effect"—it was joked that equipment broke down the moment he entered the lab.

Pauli was able to determine the rules governing electrons and the orbits they fit into. Bohr was delighted with Pauli's contribution, which he had helped to flesh out in their correspondence. This is one of many examples of protégés whose own research enhanced Bohr’s own work and added to the total body of knowledge in quantum mechanics.

Bohr helped many Danish Jews escape Nazi Germany, and later worked in a minor role on the Manhattan Project to build the first atomic bomb. Following World War II, Bohr served again as the President of the Royal Danish Academy of Arts and Sciences in Copenhagen, and was also instrumental in the formation of CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research. Niels Bohr died of heart failure at home in November of 1962.

[1] https://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Bohr_Niels/quotations/

Cover photo: Public domain

Frank Winfield Woolworth was an American entrepreneur, and founder of the F. W. Woolworth Company. He pioneered the retail variety stores which featured low-priced merchandise selling for 5 and 10 cents.