This series of articles seeks to examine the character attributes of highly successful leaders, regardless of their adherence to a strong faith or moral standard. In presenting these thoughts, Leadership Ministries is not agreeing with or advocating these traits or practices, but rather presents these as ideas for discussion and development in your own leadership journey.

Pablo Ruiz Picasso (1881 –1973) was a Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist and theatre designer who spent most of his adult life in France. Picasso demonstrated extraordinary artistic talent in his early years and was one of the most influential artists of the 20th century. His art grew increasingly abstract as he aged, using techniques including neoclassicism, surrealism and cubism. At his baptism, Picasso was christened Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Martyr Patricio Clito Ruíz y Picasso. His incredibly long name is a mixture of his relative’s names as well as saints, and Ruiz comes from his father’s name, whereas Picasso stems from his mother’s.[1]

After complications in labor, Picasso, who was extremely small for a baby, was believed to be stillborn and left on a side table while medical staff tended to his mother. It was only when his uncle, who was a doctor, blew cigar smoke and he began crying that the hospital staff realized the mistake. His uncle had saved his life.

Picasso made a number of self portraits during his life. The difference in styles is testimony to his constantly evolving expression. Photo: Public Domain

His father, who specialized in naturalistic paintings of birds, began teaching Picasso to create art from the age of 7. His father decided to give up painting when Picasso turned 14, claiming his son had become a better painter than him. For nearly 80 of his 91 years, Picasso contributed painted and sculpted works that in many ways came to define modern art. During his life his art was pioneering and controversial. But he was among the first artists to gain a worldwide following in the modern age—there are few people today who would not recognize the name “Picasso”.

Don’t fear experimentation. Picasso’s early works were very realistic. But he got bored and wanted to represent recognizable things in new ways. “This often involved showing the subject from multiple perspectives on one canvas— the front, back and side of a horse, for example,” writes Nick Sceats for Catapult. “This new way of representing things was extremely confronting and uncomfortable for people—even his closest friends and admirers initially told Picasso to stop such nonsense.”[2] Picasso rejected the naturalism that defined the Renaissance. His unique perspectives and approaches were the basis for modern abstract movements in art.

Picasso knew, though, that there were many ways to view the same thing and many ways to express himself through art. He pushed himself to innovate and see things differently. He was constantly open to experimentation. Picasso once said, “I paint objects as I think them, not as I see them.” He was a prolific artist, completing over 13,000 paintings and 100,000 engravings. He became somewhat famous for changing his techniques throughout his life. His popularity has continued to grow following his death. His least expensive painting sold for $120,000, while his most expensive sold at $140 million. Picasso experimented throughout his career. Because his works different so greatly, they had appeal to a broad range of art lovers.

Look at things from a different perspective. In a well-known story from his life, Pablo Picasso is riding in the first-class cabin of a train in Spain. A fellow passenger recognizes him, gathers up his courage, turns to the master and says, “Señor Picasso, you are a great artist, but why is all your art, all modern art, so screwed up? Why don’t you paint reality instead of these distortions?” Picasso repies, “So what do you think reality looks like?” The man grabs his wallet and pulls out a picture of his wife. “Here, like this. It’s my wife.” Picasso takes the photograph, looks at it, and grins. “Really? She’s very small. And flat, too.”[3] The artist challenged the traveler’s notion of reality. In Picasso’s thinking, all art is to some degree abstract.

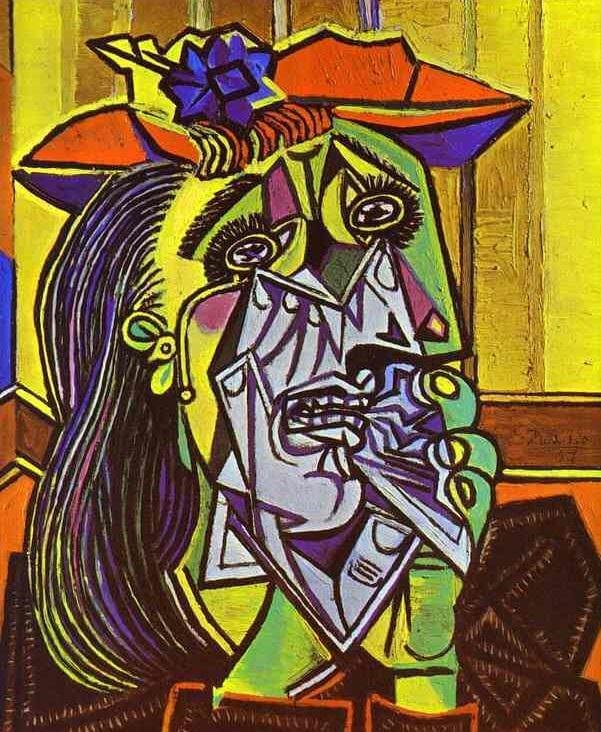

Picasso’s most famous painting is The Weeping Woman. Created in 1937, today you can view it at the Tate Modern museum in London. Photo: Public Domain

Don’t stop creating. Picasso continued to create art until his death. Even late in life, work on art energized him. Though he is known for paintings and sculptures, Picasso also did art in ceramic, drawing, watercolor, pastel, monotype, etching, theatrical design, lithography, linocut, and aquatint. He loved art so thoroughly that he would revel in exploring a different medium. Toward the end of his life, Picasso also dabbled in poetry, writing more than 300 poems. He also wrote a number of surrealist plays.

Picasso had a number of romantic interests, and fathered four children by three different women. On the morning of April 8, 1973, having entertained guests at his home for dinner the night before, Picasso died of a heart attack in Mougins, France. His second wife, Jacqueline, had a rocky relationship with the artist, but remained faithful to him to the end. Devastated by his death and lonely without him, his widow killed herself by gunshot in 1986 at the age of 59.

Frank Winfield Woolworth was an American entrepreneur, and founder of the F. W. Woolworth Company. He pioneered the retail variety stores which featured low-priced merchandise selling for 5 and 10 cents.