This series of articles seeks to examine the character attributes of highly successful leaders, regardless of their adherence to a strong faith or moral standard. In presenting these thoughts, Leadership Ministries is not agreeing with or advocating these traits or practices, but rather presents these as ideas for discussion and development in your own leadership journey.

Steve Jobs (1955-2011) was the co-founder, Chairman and CEO of Apple, Chairman of Pixar and founder, Chairman and CEO of NeXT. He is widely known as one of the pioneers in the personal computer revolution of the 1970s and 1980s and the smart phone revolution of the 2000s. iPod, iMac, iPhone, iPad, iTunes—these household words were brought as products to market under his leadership.

Make it insanely great. Jobs was a master marketer who used over-the-top superlatives to describe his products. At the 1984 launch of the original Apple Macintosh computer Jobs called it “insanely great”, a catchphrase that stuck with him for the remainder of his career. For other products he used words like magic, revolutionary, incredible, breakthrough, and unbelievable.

Jobs’ leadership at Apple resulted in some of the most widely accepted consumer technologies in the last 100 years. Jobs had a famously fanatical devotion to making great products. Author Jeffrey Young comments, “For what characterizes Apple is that its scientific staff always acted and performed like artists—in a field filled with dry personalities limited by the rational and binary worlds they inhabit, Apple's engineering teams had passion. They always believed that what they were doing was important and, most of all, fun.”

When Jobs presented a product or idea, his language and presentation confirmed his belief that what he was selling was excellent, the very best that could be made. His reputation in the office was hard driving, terse and uncompromising. He would accept nothing less than someone’s absolute best effort. As he became known for his perfectionism, customers believed him when he touted the “insane greatness” of Apple’s latest product.

Consider carefully what you say yes to. Jobs’ explanation of the importance of saying no as a leader still resonates. In 1997 at Apple’s Worldwide Developers Conference, Jobs (who had freshly returned to Apple after a multi-year exile from the company) killed off a number of popular products in development. “Focusing is about saying ‘no’”, he said. “You’ve got to say ‘no, no, no’, and when you say ‘no’, you make people mad… I know some of you spent a lot of time working on stuff that we put a bullet in the head of,” he explained. “I apologize, I feel your pain, but Apple suffered for several years from lousy engineering management.”

Jobs added, “I’m actually as proud of the things we haven’t done as the things I have done. Innovation is saying ‘no’ to 1,000 things. You have to pick carefully.” Jobs’ focus on developing particular products or features meant saying no to many great ideas that he believed would take the company away from its most important priorities. This mindset has been echoed by many other successful leaders. Billionaire Warren Buffett once said, “The difference between successful people and really successful people is that really successful people say ‘no’ to almost everything.”

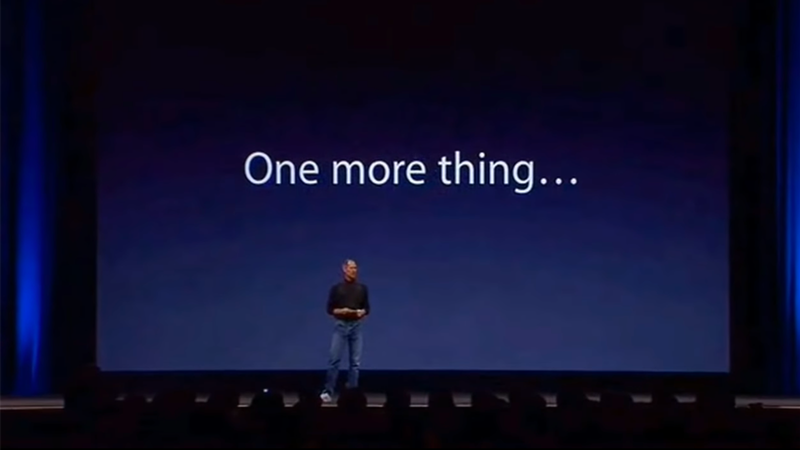

Jobs often presented new Apple products in dazzling public keynotes that became known as “Stevenotes”. Photo: Apple

Own the whole widget. While most computers of the 1980s were “beige boxes”, that comprised hardware components and software cobbled together from many different companies, Jobs’ approach was to obsess over every design detail and make as much of the device “in house” as possible. Jobs comments, “We’re the only company that owns the whole widget—the hardware, the software and the operating system. We can take full responsibility for the user experience. We can do things that the other guys can’t do.” When Steve Jobs presented a new product at large scale keynote events dubbed “Stevenotes”, he would wow the crowd with masterful presentations that showed innovative software combined with Apple’s stylish hardware. This culminated in the launch of the iPhone in 2007, a touch screen computer that could fit in your pocket, play music and movies, make phone calls and access the Internet. Within five years, every smart phone looked and tried to act like iPhone.

In the early 1990s, Apple licensed software from Adobe called PostScript that controlled its laser printers. As the desktop publishing revolution grew and Apple’s computers became known for producing high quality printed materials, Adobe controlled the key technology that made such printing possible. They continually raised prices and squeezed Apple out of the decision making in the desktop publishing market. Jobs said, “My primary insight when we were screwed by Adobe in 1999 was that we shouldn’t get into any business where we didn’t control both the hardware and the software, otherwise we’d get our head handed to us.”

Listen to your doctor. Steve Jobs died in 2011 from pancreatic cancer. The cancer was discovered in a 2003 CT scan looking for kidney stones. Instead of listening to doctors’ recommendations of immediate surgery, Jobs determined to treat his cancer as he had with every product he had ever developed. Many close to him felt Steve lived in a “reality distortion field” that simply ignored things he didn’t like in favor of his personal preferences. His capacity to create the reality he envisioned—and convince others of it—was a large part of his business success. But it was not a philosophy suited for a medical crisis.

He tried many dietary treatments and alternative methods. Of surgery Jobs said, “I didn't want my body to be opened... I didn't want to be violated in that way.” His early resistance to surgery was apparently incomprehensible to his wife and close friends, who continually urged him to do it. By the time he opted for the surgery it was too late. The cancer had spread. He abandoned his earlier homeopathic efforts and began researching and trying every experimental and cutting-edge cancer treatment available. He had a liver transplant. Though the later medications and surgeries extended his days, his early treatment mistake likely cost him his life. One wonders what would have become of the man who revolutionized the way we communicate, work and play if his life had not been cut short.

Frank Winfield Woolworth was an American entrepreneur, and founder of the F. W. Woolworth Company. He pioneered the retail variety stores which featured low-priced merchandise selling for 5 and 10 cents.