This series of articles seeks to examine the character attributes of highly successful leaders, regardless of their adherence to a strong faith or moral standard. In presenting these thoughts, Leadership Ministries is not agreeing with or advocating these traits or practices, but rather presents these as ideas for discussion and development in your own leadership journey.

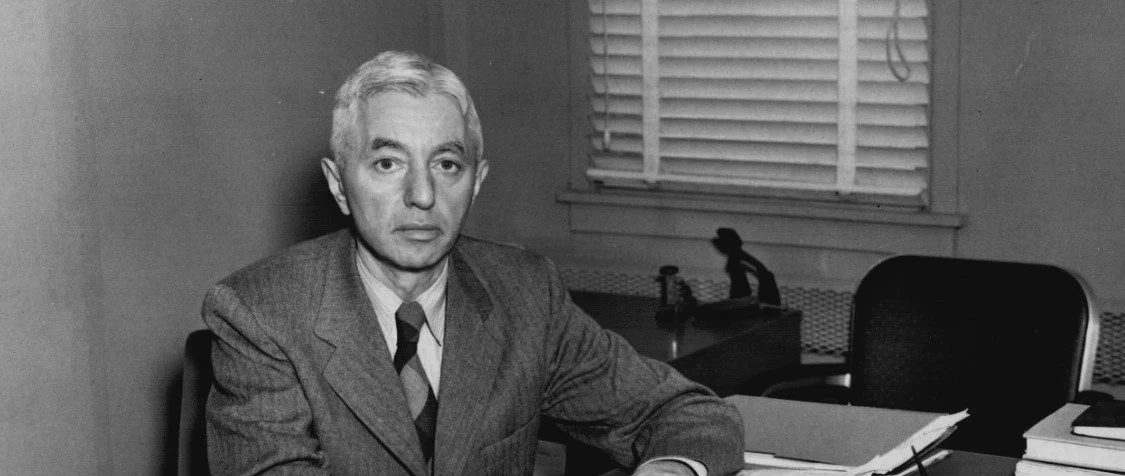

Hyman Rickover (1900-1986) was an Admiral in the US Navy and the original developer of nuclear propulsion. He served for a total of 63 years on active duty, making him the longest-serving naval officer and the longest-serving member of the US armed forces in history. He oversaw the US Naval Reactors office, which created the first nuclear powered cruisers, aircraft carriers and submarines.

Rickover was hyperactive, blunt, confrontational, insulting, and a workaholic, and was, according to biographer William Toti, always demanding of others without regard for rank or position.[1] Moreover, he had “little tolerance for mediocrity, none for stupidity.”[2] He never saw combat, and did not wear the standard uniform at all if he could help it. He was small of stature, a Jewish refugee from Poland and, for all his work altering perceptions, was not the consummate politician top military leaders often are.

Rickover developed and launched the Nautilus, the first nuclear powered submarine.

Why not the best? Rickover was a deeply polarizing figure, who expected absolute perfection from his reports and was a stickler for safety. Rickover's stringent standards are largely credited with being responsible for the U.S. Navy's continuing record of zero reactor accidents. The accident-free record of United States Navy reactor operations stands in some very stark contrast to those of the Soviet Union, which had fourteen known reactor accidents.[3]

When a little-known former Southern Governor named Jimmy Carter decided to seek the Presidency, he wrote, Why Not the Best? as a means of letting voters know his sense of values. The title comes from a question Admiral Rickover asked him during a job interview, following his graduation from the Naval Academy. “Did you do your best?” Rickover asked. Carter initially answered “yes sir” but after some thought said, "No sir, I didn't always do my best.” Describing the scene years later, Carter writes, “He asked one final question which I have never been able to forget-or to answer. He said, ‘Why not?’”[4] Rickover expected nothing less than the best of every sailor, Navy contractor, engineer and administrator he came into contact with. And they all knew it.

The Washington Post wrote of Rickover in 1981, “His ships are commanded and operated by some of the most extraordinarily able and professional men you will ever meet. Their standards, and those of many of their colleagues in other parts of the Navy, have been shaped directly and indirectly by Rickover's will and perfectionism. Yes, his standards are so high that there are only two-thirds as many such nuclear-trained officers as we need, and the ships are so expensive that we can't afford nearly enough of them. But unlike much in our modern society, and much in our military establishment, they work, and they work safely and superbly.”

Get the right people. The first thing Rickover needed to do to build a nuclear navy was to get the right people into position. He said, “Human experience shows that people, not organizations or management systems, get things done.” On the executive level, Rickover routinely went over the heads of his immediate superiors. He courted relationships with Congressmen and Senators, who gave him approvals necessary to the constant frustration of the chain of command. It was an open secret that the Navy wanted to get rid of Rickover, but they couldn’t. By the time the Navy’s nuclear ships and subs were active, he held too much power.

Further, Rickover recognized that nuclear craft didn’t need the muscular warriors of World War II, but rather smart and thoughtful engineers. As a result, Rickover personally selected every sailor tasked on a nuclear sub, and chose among the young and uninitiated, those who he knew were not already indoctrinated in traditional Navy practice.[5] Children of the influential were not selected as a matter of course, nor were people with political connections. In order to change the culture, Rickover first changed the people.

Rickover’s safety standards and processes were applied to submarine reactors like this one. When told the level of radiation that would be dangerous to a crew member, he insisted the standard would be 1/100th that amount of exposure.

Respect dangers. Rickover developed over time a group of practices he called “The Seven Rules of Success”. One of these was to “respect the dangers you face.” Many people lack respect for risk or fail to understand the dangers that they face. They tend to overestimate their risks from things that pose slight danger and underestimate the risks that matter. While we are biologically wired to respond to dangers, we aren’t too skilled at analyzing danger before it happens. Leaders must educate workers about the risks they face in the workplace and develop response plans.

In 1963 the USS Thresher, a nuclear powered submarine, sunk during a deep dive exercise. During the subsequent investigation, Rickover commented, “I knew many of the crew members personally and was responsible for their selection, training and encouragement… Everyone knows how I felt about the crew. It was a personal loss to me.” Rickover had been on the Thresher during its initial sea trials two years earlier—just as he had for every new atomic submarine since the Nautilus. When she was located at the bottom of the sea, broken apart into six sections, he wrote personal letters of condolence to the relatives of the 129 officers, crewmen and civilians who had been on board… He agonized over this loss for years, long after it had became clear that faulty welding during repairs in a Navy shipyard—something over which he had no control—was the cause of the disaster.[6]

Rickover said, “I believe it is the duty of each of us to act as if the fate of the world depended on him. Admittedly, one man by himself cannot do the job. However, one man can make a difference. We must live for the future of the human race, and not for our own comfort or success.”

[1] Toti, William. The Wrath of Rickover. USS Hyman G. Rickover Commissioning Committee. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

[2] Hadden, Briton; Luce, Henry Robinson (1954). Time. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hyman_G._Rickover

[4] https://www.amazon.com/Why-not-best-Jimmy-Carter/dp/0805455825

[5] https://www.forbes.com/sites/kevinkruse/2015/01/06/leadership-lessons-from-admiral-rickover/

[6] https://www.raabcollection.com/john-f-kennedy-autograph/john-f-kennedy-signed-wake-first-loss-nuclear-submarine-pres-john-f-kennedy